Kim Henson sheds light on a seldom-told pre-War success story for the Standard Motor Company…

Kim Henson sheds light on a seldom-told pre-War success story for the Standard Motor Company…

(Words and all photographs by Kim).

Complex and very wide-ranging, the ‘Flying’ Standard line-up found buyers galore keen to own the boldly styled models. This is what happened…

Since the last Standard-badged car for the UK was produced well over half a century ago, it is perhaps unsurprising that today many people know little of the firm and its well-respected vehicles that were built over a 60 year period. Many will also be unaware that contributing to the company’s great success during the 1930s – ultimately helping it to survive until 1963 – was the remarkable range of ‘Flying’ Standard models…

Yet from late 1935 until the outbreak of the Second World War, the Flying Standards range took the British motoring world by storm, introducing a rapidly-changing abundance of radically-styled yet user-friendly new family cars.

Within just four years the range grew and diversified to offer models across the spectrum from economy cars to mid-range saloons and dropheads to fast luxurious vehicles, within a line-up that was refreshed very frequently. The strategy worked, with the new Flying models arriving in quick succession and providing broad appeal to buyers, thus enabling the Standard firm to survive, thrive and prosper.

DARKNESS TO LIGHT

Formed in 1903, the Coventry-based Standard Motor Company came very close to going out of business during the lean years of the late 1920s. However in 1929 the arrival on the Standard scene of John Black (previously at Hillman) started the firm’s turn-around from near meltdown in financial terms to a profitable business.

During the tough economic times of the late 1920s, the market for large cars that were expensive to buy and to run all but disappeared, together with many of the car manufacturers producing such vehicles. In addition to the high cost of acquisition, unaffordable for most people, large vehicles also attracted high rates of road tax…

In the early 1930s Standard’s main competitors were Austin, Ford, Morris, Hillman and Vauxhall (Singer, Triumph and others were also battling for market share). All these firms were starting to revise their product ranges and aiming at the mass market for affordable vehicles. Therefore, in order to compete and prosper Standard needed a compact yet accommodating family vehicle that was sensibly priced, inexpensive in road tax and running costs, and reliable. The result was the new Standard Nine, brainchild of Chief Engineer Albert Wilde and notable for its worm-driven rear axle.

With John Black guiding the company, the sales success of the well-received Nine (plus new 10hp and 12 hp family saloons which soon followed) meant that cash became available to develop fresh models through the early 1930s, including the sales success masterstroke of the new Flying Standard range introduced to the world at the Olympia Motor Show in October 1935.

At that time Standard’s more traditional models – worthy, well-respected and still liked by buyers – were also still available, with the firm’s simplified 1936 line-up having been announced in August 1935 and comprising the Nine, Ten, Light Twelve, Sixteen, Light Twenty and Twenty.

However, Standard’s fortunes were to move up a gear with the introduction of the boldly-conceived new Flying models, widely considered the stars of the 1935 Olympia Show… and indeed the new range soon helped Standard become one of the ‘big six’ car makers in Britain.

A NEW ERA

The new cars arrived at a time when for many people in Britain economic prospects were improving, and car ownership became a possibility even for families of relatively modest means. Motoring became an enjoyable free time occupation for many, enabling families to ‘escape’ to the countryside or the coast, and to visit relatives and friends who lived some distance away. Thus there was an increasing demand for affordable, reliable vehicles to fulfil these roles, and for car makers realising the new potential, sales success was there for the taking.

During the mid-1930s the models sold by most British manufacturers, including Standard, still had a predominantly ‘perpendicular’ appearance, although styling lines softened generally as the decade progressed.

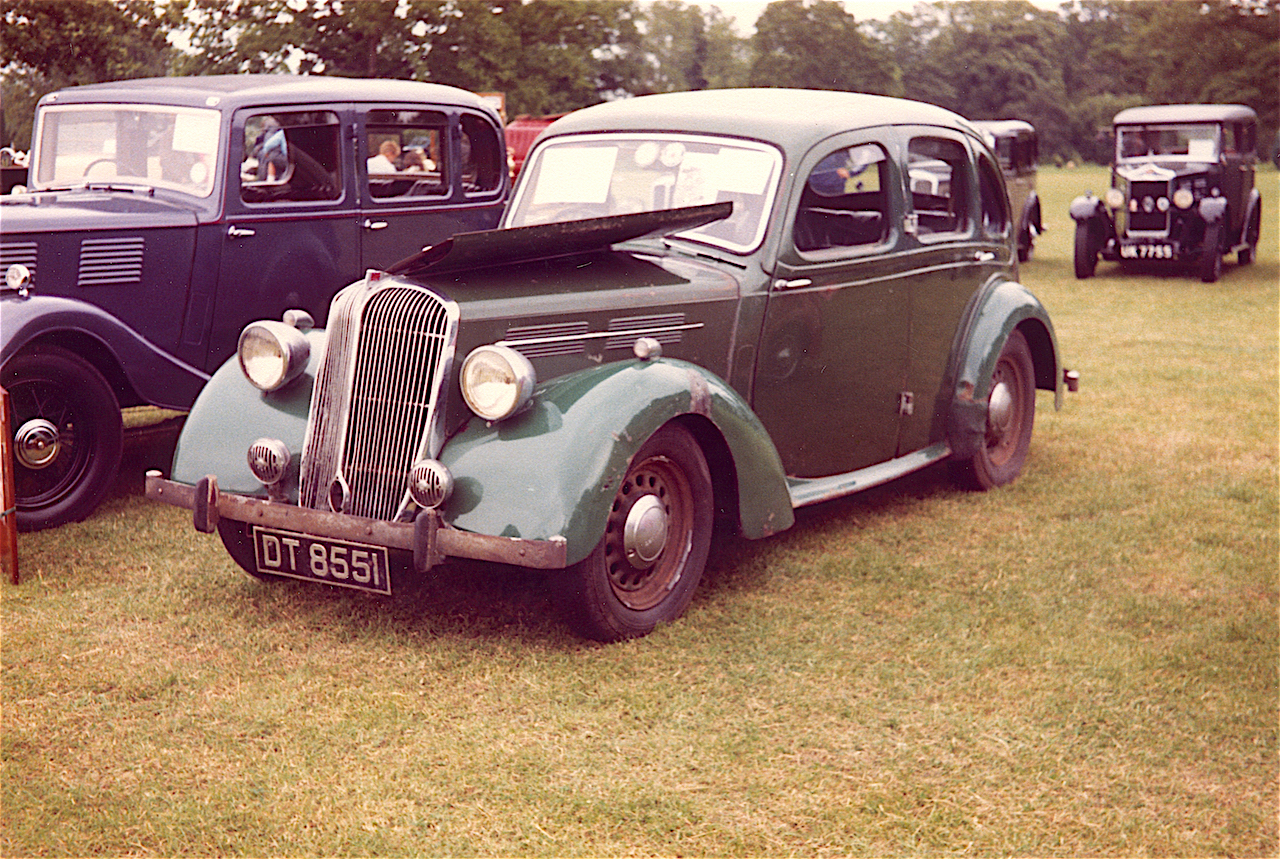

By contrast the new Flying Standards featured boldy-styled all-new bodywork with deliberately flowing lines from nose to tail, and incorporating sharply sloping rear panelwork. The distinctive and dynamic attention-grabbing styling of these new kids on the block at once made the cars stand out from contemporary rivals.

The new designs were well-received by the motoring press and buying public alike, at a time when ‘streamlining’ was becoming fashionable for cars, aeroplanes and boats of the new era just dawning.

STANDARD FLYING TWELVE, SIXTEEN AND TWENTY

The first three Flying Standards, unveiled at the 1935 Olympia Show, were the four cylinder, 44 bhp 1.6 litre (1608cc) Twelve (model designation A12S), and a choice of six cylinder models between the 56 bhp 2.1 litre (2143cc) Sixteen (A16S) and the 64 bhp 2.7 litre (2664cc) Twenty (A20S). All the engines used in these new models were sidevalve units and all incorporated an aluminium cylinder head, a water pump and a thermostat for better temperature control.

The rear wheels were driven via a four speed gearbox with effective synchromesh on the upper three ratios, and for its time this has always been regarded as a particularly smooth-changing unit.

Semi-elliptic leaf springing was used at the front and rear, steering was by a Bishop cam and lever steering box, and Bendix ‘duo servo’ brakes were fitted.

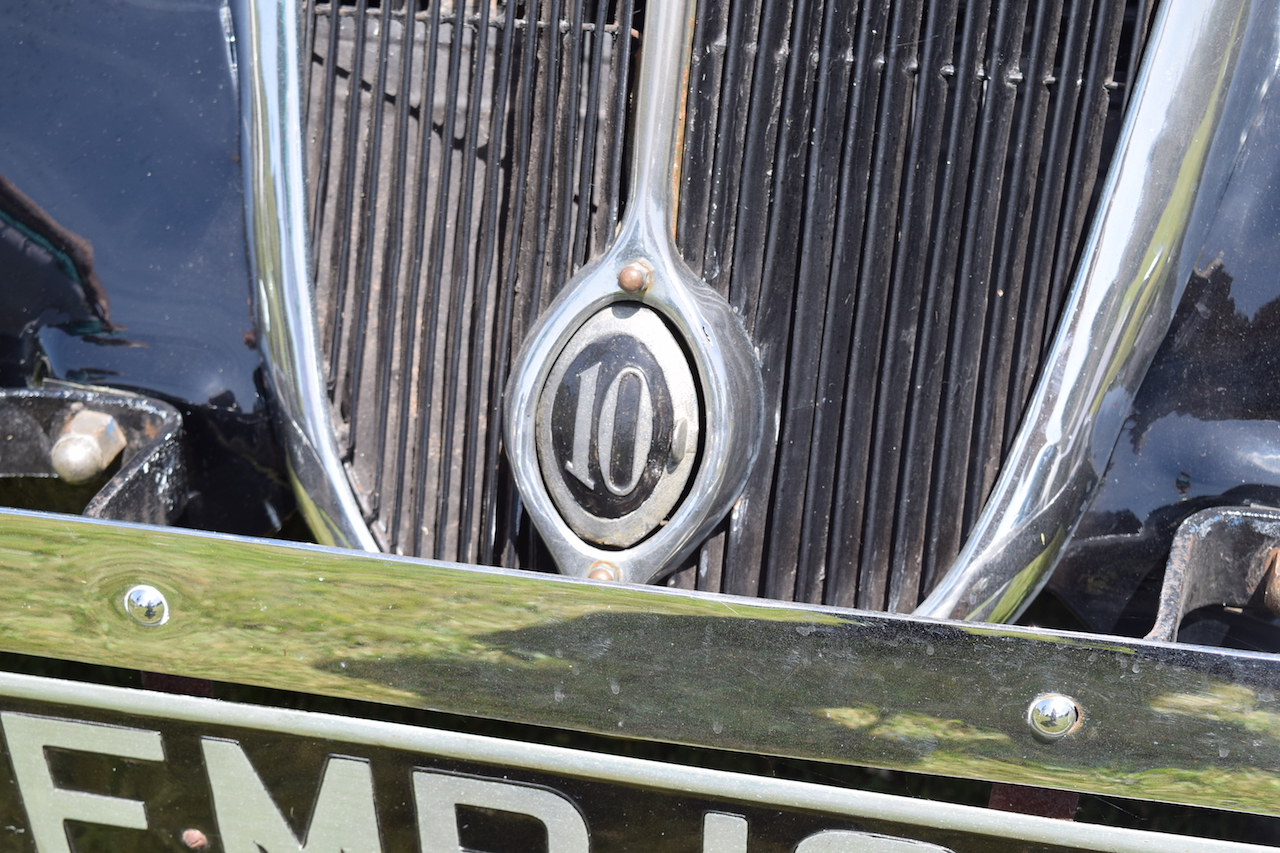

The new Standards featured separate, traditional type chassis frames carrying the bold new bodywork, which in each case was fronted by a distinctive slatted grille assembly, with the vertical painted steel slats positioned within an angular chromed surround. For each model the R.A.C. taxation system ‘horsepower’ rating was denoted on a hinged cover for the starting handle aperture (12, 16 or 20).

The body shells were similar for all three models, but the bonnets (and wheelbase dimensions) of the six cylinder cars were longer than those of the Twelve, to accommodate the bigger engines.

Helping the sleek appearance of all the new cars were detachable Wilmot-Breeden wheel trim discs (covers), hiding the 17 inch wire spoked wheels.

In each case the bodywork incorporated four doors, all hinged at the rear, and a luggage compartment built into the car’s sloping tail (at a time when most family cars did not have a boot at all). Accommodation for the spare wheel was provided within the base of the boot, the lid of which was hinged at the top.

The specification of the range-topping Flying Twenty included two factory ‘fitted’ suitcases, designed to fit snugly within the boot (these could be optionally specified by buyers of the Twelve and Sixteen models).

Comprehensive equipment in all three models included leather upholstery, an automatically-activated reversing lamp, a telescopically-adjustable steering column, a ‘built-in’ jacking system, a steel sliding sun roof, and beautifully crafted folding picnic tables, built into the backs of the front seats.

Instrumentation included an ammeter, an oil pressure gauge and a coolant temperature gauge.

Accommodation for front and rear passengers was generous in terms of head and leg room, and the car’s flat floors, with an absence of footwells, aided entry to and exit from the vehicle. The comfort provided by the seats and the ride quality were exemplary for the time.

There was plenty of stowage space within the vehicle, in the form of front and rear parcel shelves, plus elasticated pockets built into the door trim panels.

Roadholding and handling characteristics were on a par with those of competitor vehicles in the mid-1930s.

The vehicles were not lightweights, with even the Twelve weighing in at 23.75 cwt (1,207 kg), while the Sixteen and Twenty weighed 25.75 cwt (1,308 kg). Nonetheless, in each case performance was considered good, with a top speed available for Twelve owners of 68 mph, with 72 mph and 76 mph provided by the Sixteen and Twenty respectively.

More importantly for most owners was a happy, unstressed cruising speed on open roads of between 45 and 55 mph for the Twelve, and 50 to 60+ mph for the six cylinder models. For the mid-1930s these were competitive figures.

Fuel consumption was typically 24 to 28 mpg for the Twelve, and around 19 to 24 mpg for the six cylinder models.

NEW TEN AND TWELVE

Throughout the next four years, the Flying Standard line-up rapidly changed and expanded, starting with two new versions that were introduced in March 1936…

The new Flying Ten (A10S model and retrospectively known as the ‘Mark I’) and the new Flying Light Twelve (AL12S) were externally more compact than the first models, being shorter, less wide and lower. However they shared the ‘family’ resemblance, and interior space was almost as good as in the first Twelve, Sixteen and Twenty ‘Flyers’.

Both the new models featured the same modern body shell, mated to a cleverly-designed chassis assembly, and the cars’ sills effectively formed the outer longitudinal members of the chassis frame. Importantly, this set-up was immensely strong but also helped to save weight, with both the newcomers weighing in at 20 cwt (1,016 kg). This helped to improve performance and fuel consumption.

For the record, compared with the original Twelve (which then became known as the ‘Heavy’ Twelve), the Light Twelve was 3.75 cwt (about 178 kg) lighter, representing a weight saving of approximately 16 per cent.

Under the bonnet of the Light Twelve was virtually the same 1608cc engine as used in the first Flying Twelve, but with a slightly lower compression ratio and producing 42 bhp (against 44 bhp). With a final drive ratio of 4.71:1 this gave a quoted top speed of 72 mph.

By contrast the new Ten was powered by a generally similar engine but with a reduced cylinder bore diameter, to provide 1343cc and 35 bhp. With a lower final drive ratio of 5.43:1 this model was said to be capable of 65 mph.

For both cars the overall fuel consumption was typically 28 to 30 miles per gallon.

As well as being smaller than the first ‘Flyers’, the new Ten and Light Twelve featured several bodywork differences, notably lacking running boards and with the front and rear doors all hinged from the centre pillars, rather than having all the doors hinged at their rear edges. In addition the boot lid was now hinged at its base, and smaller diameter wheels (16 inch instead of 17 inch) were fitted. These were now of the pressed steel ‘Easiclean’ type, rather than spoked wire wheels.

Slightly less elaborate interior treatment was applied to the new models, and individual front seats replaced the bench type front seats on the earlier cars.

It should be mentioned that while some running gear details (including brake and steering box set-ups) varied according to individual ‘Flying’ models over the next few years, under John Black’s guidance all versions deliberately conformed to the same winning formula of providing a stylish, affordable, dependable, comfortable, easy to drive vehicle that also delivered impressive performance against competitor cars that buyers might consider.

SMALL BUT PERFECTLY FORMED NINE

The 1936 Olympia Motor Show saw the arrival of Standard’s 1937 line-up (now all ‘Flying’ models), including the new two door Flying Nine (9A), aimed at cost-conscious families who might be considering small cars from other manufacturers, and providing more generous than usual accommodation for four adults within a compact body shell. ‘Basic’ and De Luxe variants were offered, De Luxe versions featuring leather upholstery and a host of other ‘extras’.

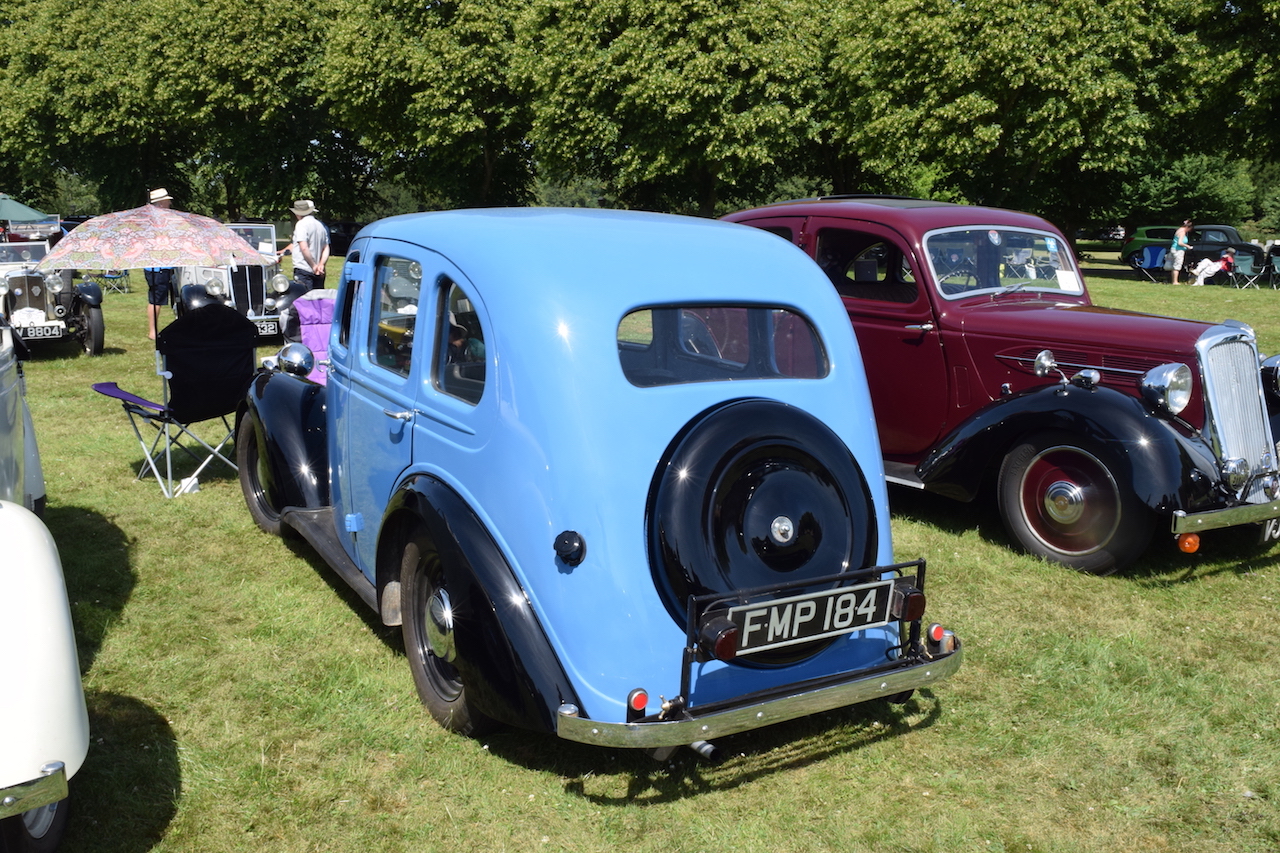

From the front, the new car was generally similar in appearance to the larger Flying Standards, but the spare wheel was mounted externally on the rear bodywork (and featuring a circular steel cover, on De Luxe versions).

Although smaller than its stablemates, the Nine was a comfortable and comprehensively-equipped car. Unlike its bigger brethren, it did not have a luggage boot accessed from outside the vehicle, but did incorporate a compartment reached by folding forward the rear seat back. In addition, on De Luxe versions an external folding luggage rack was provided, attached to the rear bumper.

Like the Ten, it was powered by a four cylinder sidevalve engine, but in this case with a capacity of 1131cc and developing 30 bhp. This was sufficient to endow the compact newcomer with a top speed of 60 mph and touring petrol consumption of around 36 mpg.

The Nine cost £149, or £159 in De Luxe form. This compared with the much larger Ten which in the spring of 1936 weighed in at £199, while the original asking figure for the Light Twelve was £205.

A NEW FLYING TEN (‘MARK II’)

Leaving behind the short-lived first Flying Ten (A10S) and Light Twelve (AL12S), at the 1936 Olympia Show the Standard company showed a new Flying Ten (10AL ‘Mark II’ version).

Built on the same chassis as the Nine, although with a wheelbase five inches (about 125 mm) longer, and thus providing greater leg room for rear seat occupants, the new Ten featured four doors, all of them hinged on the centre pillars. However the bodywork was built on the same visual theme as the Nine. In the same style the Ten’s spare wheel was mounted externally at the rear and the luggage compartment reached by folding forward the rear seats.

Under the bonnet was a larger cylinder bore version of the Nine’s engine, developing 33 bhp from its 1267cc. This provided a top speed of 65 mph and, with the new car weighing about 1.5 cwt (76 kg or so) less than the first Flying Ten, it was a more sprightly performer.

Buyers were asked to pay £20 more for the new basic and De luxe versions of the Ten, compared with those of the Nine, so £169 and £179 respectively. These figures were very competitive; as just one example the contemporary 1937 Austin price list shows their Ten Cambridge models offered for £185 for the basic fixed-head model, or £195 for the sun roof version.

NEW FLYING TWELVE AND FOURTEEN – PLUS A V8 POWERED MODEL!

For 1937 the Light Twelve (AL12S) was discontinued, with a new Twelve (12AL) in effect being a revised version of the Light Twelve, but with minor changes, for example alterations to the front grille, the addition of window louvres, etc. Customers could choose the familiar 1608cc Twelve engine, or could opt for the first Ten’s 1343cc motor (versions thus equipped were designated 10A).

Gone too was the Sixteen (A16S), but in came a new model, the Fourteen (14A). In terms of bodywork this was generally similar to the original (‘Heavy’) Twelve, but the new car was powered by a 1776cc engine producing 49 bhp, or customers could alternatively specify the 1608cc Twelve engine (cars thus fitted were designated 12A).

By contrast with the wire wheels and cover discs of the Heavy Twelve, the wheels on the new Fourteen were Easiclean types. These incorporated threaded lugs for the new style of hub caps, secured by two screws and used for the first time by Standard (they were only ever used on the Fourteen and Twenty models from 1937 to 1939).

The only six cylinder Flying Standard in the 1937 line-up was a new Twenty, powered by a 2664cc engine that was effectively ‘one-and-a-half’ Fourteen motors.

Not content with building a six cylinder Twenty, Standard went one better and unveiled a V8 powered Twenty (20V code) at the 1936 Olympia Show.

This car, the ‘V-Eight’, with bodywork quite similar to that of the latest Twelve, featured a new, broad ‘waterfall’ style front grille unique to this model (although in revised forms it was later adopted for all lower-powered Flyers), and was propelled by a 2686cc motor, in which the two cylinder banks (effectively two of the original Ten’s 1343cc cylinder blocks) were joined at their base in a 90 degree angle.

This was a potent vehicle for its time, the V8 motor delivering 75 bhp at 4,000 rpm and giving the car a nought to 60 mph acceleration time of 18 seconds and a top speed of 80 mph. Such figures may seem tame today, but were virtually unheard of for family saloons of that era.

Touring fuel consumption was in the order of 20 miles per gallon.

The car was expensive at £349 for the saloon, albeit later reduced to £325 (or £359 for the Drophead Coupé version), compared with £299 for the six cylinder Twenty saloon. Road tax costs for the V-Eight were also considerable under the R.A.C. ‘horsepower tax’ system…

This helps to explain why the ‘V-Eight’ was produced in very small numbers, and it is believed that just 350 or so found buyers.

1938 MODELS AND ‘WATERFALL’ GRILLES

As the 1930s progressed World War II clouds were gathering as Standard’s fortunes continued to improve and the company thrived, with its well-liked and now comprehensive ‘Flying’ range finding favour with more and more buyers.

(Historical note: To help with the War effort, and in particular to enable aircraft production to be optimised, as with many other British motor manufacturers the Standard company was involved in the government’s ‘Shadow’ factory scheme. The vital creation of ‘Shadow’ (duplicate) factories enabled aircraft production to be increased in readiness for the expected outbreak of hostilities. However, that’s another fascinating story and this article necessarily concentrates on the cars…).

In the spring of 1937, the chromed grille surround was changed on all ‘Flyers’ to incorporate a prominent enamelled ‘Union Flag’ at its top, in place of the lower profile grille motif and winged badge used hitherto.

However the grille design was soon changed again, for the 1938 model year, across the range… The fresh ‘waterfall’ style grilles were generally similar to the type first used on the V-Eight Twenty, but not as wide. Notably they incorporated vertical chromed steel slats with swept-back/‘rounded’ tops, located within a painted steel surround/shell – except on the V-Eight Twenty, which had a chrome-plated surround. All models featured the Union flag arrangement (as previously used on March to May 1937 models) at the top of the new grille.

Introduced during 1937 for the 1938 model year were three new Flying Standard models. One of these newcomers was a four seater, two door Drophead Coupé version of the Flying Twelve, with bodywork by Mulliner…

The other two newcomers for 1938 were so-called ‘Touring’ versions of the Flying Fourteen and Twenty saloons. These comprehensively equipped, luxuriously-trimmed vehicles were identifiable by their distinctive ‘notch back’ styling, incorporating a larger luggage boot than the previous ‘beetle back’ style Fourteen and Twenty models. At first the Touring saloons were sold only with ‘four light’ bodies, with a side window in each of the four doors, but without a window in the rear ‘quarter’ panel. However, an additional new ‘six light’ version made its debut at the first Earls Court London Motor Show in 1937, featuring an additional opening side window just behind each rear door.

Revised interiors and new pastel colours (on some models) were also introduced for 1938.

The model range now consisted of the Nine (designations 9BA/9B), Ten (10BLA/10BL), Twelve (12BL or, in examples equipped with the Ten engine, 10B), Fourteen (14BA, or 12B when fitted with the Twelve motor, or 14B in the case of the Touring Saloon version), Twenty (20BA, or 16B when powered by the Sixteen engine), and the V-Eight Twenty (20V).

Drophead coupé bodywork was offered on the Twelve, Fourteen and V-Eight chassis, with a variety of coachbuilders being involved, according to the model.

A new ‘notchback’ style Twelve Super saloon (12CB designation) and a Drophead Coupé version were introduced in March 1938, featuring a chrome-plated grille surround and a centralised running gear lubrication system.

In July the same year, new Fourteen and Twenty Super saloons arrived, also equipped with the centralised lubrication arrangement.

THE 1939 RANGE – AND INDEPENDENT FRONT SUSPENSION

The 1939 line-up of Flying Standards was introduced in September 1938, with a brand new ‘economy’ or ‘budget’ four seater saloon, the Eight (designation 8A) making the headlines. This newcomer was aimed at providing the Eights from rival manufacturers (notably Austin, Morris and Ford) a run for their money. The new model was also produced in four seater Tourer form (with bodywork by Carbodies), and for the 1940 model year, introduced in September 1939, was available as a Drophead Coupé (bodywork by Mulliners of Birmingham). This too was a four seater but with a more sophisticated hood set-up than the Tourer, and with winding door windows…

Under the bonnet of Standard’s Eight was a smaller bore version of existing Flying Standard four cylinder engines, providing a capacity of 1021cc and a power output of 31 bhp, actually a touch more than the 30 bhp of the Nine (although the Nine was later uprated to 33 bhp).

Since the Eight was considerably lighter than the Nine (around 14 cwt compared with 17 cwt or so) the Eight provided more lively performance, plus a top speed in excess of 60 mph. It was a very economical car too, with touring fuel consumption in the region of 45+ miles per gallon.

Although the Eight was a compact vehicle (and shorter than the Nine), there was plenty of room for four adults within the ‘notchback’ bodywork, which also incorporated a separate luggage boot accessed from outside the car, via a bootlid hinged at its bottom edge.

Very big news for Standard was the adoption for the new Eight of independent front suspension, which was most unusual in British cars at that time, and especially so in inexpensive or small models. The system made use of a transversely-mounted semi-elliptic leaf spring, and improved the car’s ride comfort and dynamic behaviour.

By contrast, the penny-saving use in the Eight of six volt electrics and a three speed gearbox were retrograde steps, as all the other Flying models shone more brightly on 12 volts, and were equipped with four speed gearboxes. On the other hand, the Eight was very competitively priced at just £129.

New ‘notchback style’ Flying Ten (10C) and Twelve (12C) models were also announced for 1939, and like the new Eight, both these models rode on independent front suspension. All three cars also featured a revised chassis, which featured box section side rail assemblies. All also had a luggage boot accessed from outside the car.

The independent suspension set-up was becoming the norm but, for example, the new Nine Super saloon (9CB, which did feature ‘notchback’ bodywork) the Twelve Super and both the Fourteen and Twenty Touring Saloons still all had conventional longitudinally-mounted front leaf springs and non-independent suspension. The Nine Super gained independent front suspension for the necessarily short-lived 1940 model year.

For all 1939 models from the Twelve upwards, the grille surround/shell was changed from a painted type to a chrome-plated variety, although the main part of the grille itself remained as before; this feature was first seen on the V-Eight Twenty for 1937. A four door version of the Eight was introduced in January 1940, but few were built before civilian motoring was curtailed for the duration of World War II. (While not the subject of this article, the Standard Motor Company made a huge contribution to the War effort in terms of producing military vehicles and aircraft engines, plus a host of other hardware).

A four door version of the Eight was introduced in January 1940, but few were built before civilian motoring was curtailed for the duration of World War II. (While not the subject of this article, the Standard Motor Company made a huge contribution to the War effort in terms of producing military vehicles and aircraft engines, plus a host of other hardware).

EVEN MORE PRE-WAR VARATIONS ON THE THEME

In addition to the mainstream models, some fascinating low-volume variants of the Flying Standards were produced during the late 1930s, including, for example, Avon-bodied and Stanhope Drophead versions. A compact front wheel drive saloon was also under consideration by The Standard Motor Company…

POST SCRIPT: POST-WAR DERIVATIVES – THE FLYING STANDARD STORY ENDS

When the Second World War ended, British car makers – including Standard – were keen to get their production lines rolling as soon as possible, and the easiest way to do this was to re-introduce pre-War models, albeit mildly amended.

When the Second World War ended, British car makers – including Standard – were keen to get their production lines rolling as soon as possible, and the easiest way to do this was to re-introduce pre-War models, albeit mildly amended.

Standard simplified their line-up and concentrated on re-introducing the Eight, now powered by a slightly smaller capacity engine of 1009cc in conjunction with a four speed gearbox (model designated 4/8A), plus a revised Twelve (12CD) and Fourteen (14CD). These two larger cars now shared the same new body. This looked generally similar to that of the 1939 Flying Twelve, but was three inches (about 75mm) wider than the pre-War version, and there were many other minor revisions. For both the new Twelve and Fourteen the doors were hinged from the centre pillars.

A significant identifying feature of all the post-War versions is that they lack the louvres which were incorporated within the bonnet sides on the pre-War ‘Flyers’ (so the bonnet sides on 1946 to 1948 cars are plain). The bumpers on the post-War Twelve and Fourteen are also much deeper than those of the 1939 Twelve, and the wheels on these two larger post-War cars are pressed steel types with long, narrow radial slots, as opposed to than the multi-hole pre-War style.

The Eight was offered as a saloon, Tourer or Drophead Coupé, but for buyers of the Twelve and Fourteen the choice was between four door saloon or Drophead Coupé versions only. These cars were sold until 1948.

Technically these post-War models are not termed ‘Flying’ Standards as the name was dropped for these derivatives. However, all the revised versions were very much based on the pre-War cars, and although starting to look old-fashioned by the time of their discontinuation in 1948, served the company well until a bold ‘one model’ policy was implemented by Sir John Black (he was knighted in 1943). The resulting Vanguard was announced in July 1947 and was another milestone success story for the company.

RIVAL MODELS?

Through the late 1930s, rather than spending their cash on a Flying Standard, new car buyers could opt for competitive models from Austin, Ford, Hillman, Morris or Vauxhall, or from the slightly less mainstream Rover, Singer or Triumph. The cars from all these contemporary rivals had their respective merits in different ways (and indeed still do, as classic buys).

However it is true to say that the models under review produced by the Standard Motor Company justifiably earned a reputation for high quality, dependability and good value for money, and they were generally highly regarded by owners.

ON THE ROAD TODAY – AND KEEPING THEM RUNNING

Surviving Flying Standards may be from another era but they are still capable of ‘sympathetic’ enjoyable use, including long-distance trips, and are all family-friendly and as practical as 1930s vehicles can be 80 years or more down the line.

Surviving Flying Standards may be from another era but they are still capable of ‘sympathetic’ enjoyable use, including long-distance trips, and are all family-friendly and as practical as 1930s vehicles can be 80 years or more down the line.

In their heyday they were widely praised by the press and buyers for their good performance, impressive dynamic behaviour and smoothness of running. The four speed gearboxes used on all versions except the pre-War Eight came in for particular mention as excellent examples of their type, with effective synchromesh on the upper three ratios and a slick-operating gearchange. Such comments still apply, when comparing these Standards with other classics of a similar age. Of course these cars are getting on in years and need careful attention in terms of regular frequent maintenance, especially engine oil and filter renewal and replenishment of the multitude of running gear greasepoints. However such work does not take long and will be repaid by a Standard that will run happily for many years without major attentions being required.

Of course these cars are getting on in years and need careful attention in terms of regular frequent maintenance, especially engine oil and filter renewal and replenishment of the multitude of running gear greasepoints. However such work does not take long and will be repaid by a Standard that will run happily for many years without major attentions being required.

It should also be mentioned that it is imperative that the mechanically-activated brakes (cable/rod, depending on model) are in excellent condition AND correctly set up. Neglect in this area can result in heart-in-the-mouth situations, but when in good order and properly adjusted the brakes can be highly effective for cars of this age.

Most routine attentions are straightforward for the do-it-yourself enthusiast, and once the car is in good condition, looking after a Flying Standard is not difficult nor overly time-consuming. However… It is wise to plan ahead in obtaining spares, especially for major operations, as some replacement components are scarce and not easy to source in a hurry.

THE STANDARD MOTOR CLUB

While of course it is possible to buy and run a Flying Standard (or post-War derivative) without being a member of the Standard Motor Club, I strongly advise owners/enthusiasts of these models to join the Club – even before buying a car.

The organisation provides a spares service for its members, which is very useful and some items have been remanufactured. However, equally important is the huge amount of experience, information and enthusiasm among fellow owners/members of the Club, not to mention the camaraderie that exists between people of like minds and with similar vehicles.

Personally, in the case of my own Flying Standard, from fellow members/owners I have found a willingness to help others that is heart-warming! Quite simply, were it not for the Club and its members I would not have been able to keep my car on the road.

Many enjoyable Club events/get-togethers are also available to the owners of Flying models as well as members who own any of the Standards built by the company during its 60 year history.

To find out more, please go to: https://www.standardmotorclub.org.uk/

The Club Secretary is: Lynda Homer: 43, The Ridgeway, St. Albans, Herts, AL4 9NR, England. Tel: (01727) 868405.

VERDICT

The Flying Standards were popular, dependable, well-liked cars that sold well and were responsible for consolidating the company’s position as it climbed further out of the economic mires it had experienced in the late 1920s/early 1930s, and then prospered.

The wide variety of different models introduced in the space of just a few years was extraordinary, but this approach kept the range fresh and appealed to buyers keen to obtain the latest version.

The Flying Standards were ahead of their 1930s era in terms of dynamic styling and performed well for their time, also incorporating many new features ahead of their rivals. For example, aluminium cylinder heads, pump-assisted coolant circulation and independent front suspension were fitted on the ‘Flyers’ long before these aspects became commonplace on other British-built cars.

THANK YOU

My grateful thanks to the Standard Motor Club members and other owners of Flying Standards for their cheerful assistance with information and for happily allowing me to photograph their cars to help me tell the story of this fascinating range of vehicles.

Kim Henson.

Kim’s interest:

Kim’s family has owned a variety of Standard models since the mid-1930s, starting with his grandfather, and there has been at least one Flying Standard in his family at all times ever since 1948! Kim currently owns a much-loved 1938 Flying Fourteen Touring Saloon that he bought in 1991 and it has been a family favourite classic ever since.