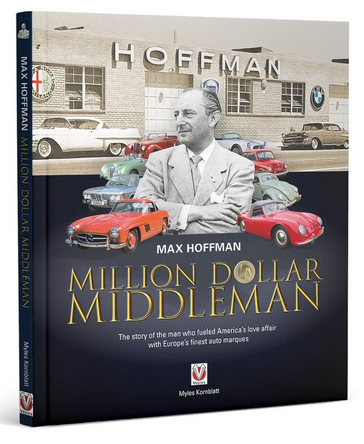

For Your Bookshelf – Max Hoffman: Million Dollar Middleman

Reviewed by Kieron Fennelly

Author: Myles Kornblatt

Published by: Veloce; https://veloce.co.uk/

160 pages (hardback)

UK List Price: £30.00 ($50)

ISBN: 978-1-787115-03-3

Max Hoffman is well-known as the entrepreneur who introduced various European manufacturers to the USA in the post war years. Author Kornblatt recounts how Hoffman fled Austria when the Nazis took over in 1938, and established himself in the US. Once the war was over, he resumed his previous business of importing and selling cars.

He is best known for creating a foothold for Jaguar, Porsche, Mercedes and BMW, but also tried with VW and Fiat though his predilection was prestige rather than more mass-produced cars which were also less lucrative. The author describes how Hoffman kept his Mercedes business separate from Jaguar by operating under a different name – William Lyons would never have tolerated representation shared with his main rival.

The same sleight of hand by which Hoffman would advertise cars he had neither in stock, nor could obtain (such as Rolls Royce) was apparent in the very tight distribution contracts he drew up to hedge himself in. When manufacturers finally outgrew his distribution capabilities (he was never properly committed to aftersales service) or tired of his deceptions, the relationship was almost always terminated with a huge pay-off in Hoffman’s favour. When he finally parted with BMW after representing Munich for 15 years, BMW paid him some $23m.

Kornblatt does confirm that Hoffman did have considerable design influence, but only with certain manufacturers. He certainly convinced Ferry Porsche to build the cut-down Porsche Speedster, but also points out that although Hoffman lobbied strongly for the BMW 2002 (i.e. the 1600 coupé with a 2 litre engine) this car cannot be attributed to him alone – BMW already had the model up its sleeve. With Mercedes he tried hard to persuade the Germans to build a model between the exclusive 300SL and the saloon-based 190SL. But heavy and slow though the 190SL was, Mercedes would not budge, yet it sold well in the US.

VERDICT

There is nothing really new in Kornblatt’s account: Hoffman is confirmed as the highly sophisticated wheeler-dealer of general perception and very little is disclosed about the man himself who appears a distinctly one-dimensional character. Was his motivation any more than simply making money? As the book shows, he certainly had a taste for architecture to match his feel for what the American car-buying public wanted, but the author does not attempt to explore these facets. At 160 pages, two thirds of which are taken up by illustrations, not all of them relevant, the work is disappointingly short. The Hoffman story is a fascinating chapter of automotive history which deserves a more substantial account.