Kieron Fennelly reads the amazing story of what actually happened in BMC’s Competitions Department in the 1950s and 60s, written by those who were there at the time…

Kieron Fennelly reads the amazing story of what actually happened in BMC’s Competitions Department in the 1950s and 60s, written by those who were there at the time…

Authors: Marcus Chambers, Stuart Turner and Peter Browning

Published by: Veloce: www.veloce.co.uk

640 pages (hardback)

UK Price: £25.00 ($39.95 US)

ISBN: 978-1-845849-94-8

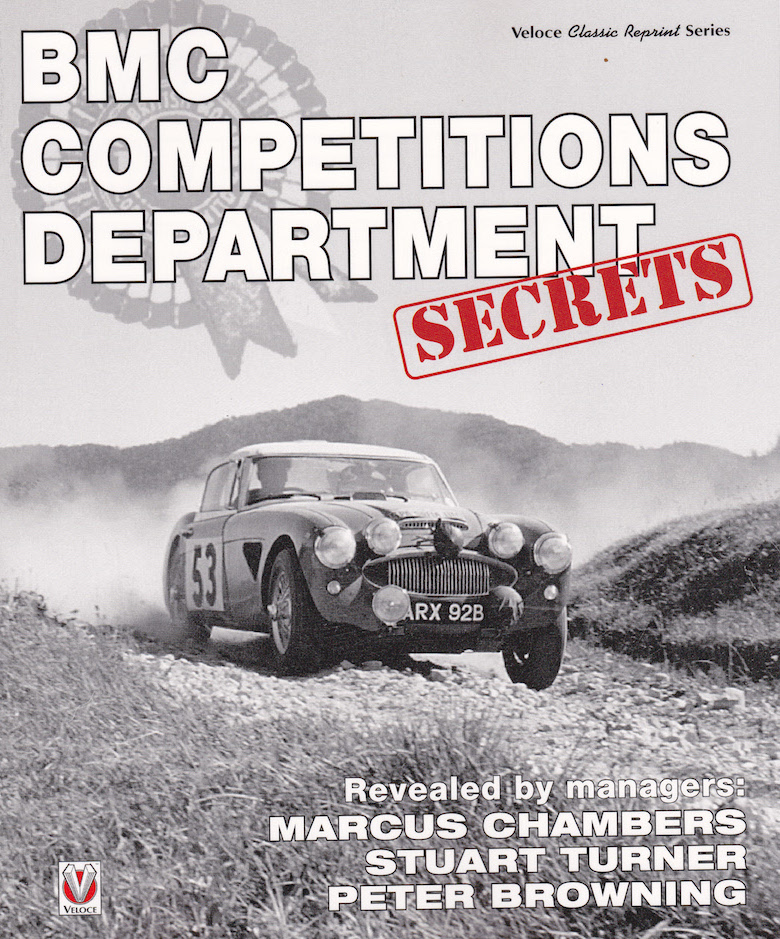

This book is essentially a pictorial history of BMC’s competition cars of the 1950s and 60s. The pictures are accompanied by press releases of results and correspondence of the team managers between their rally drivers and to BMC management. The three team managers are of course Marcus Chambers, Stuart Turner and Peter Browning and each writes an all too short commentary on his stint in the job.

Chambers set the ball rolling in 1955 and by 1961, having pressed into service almost every car in the BMC range, he had generated a remarkable amount of publicity for the company. It mattered little that this was more of the ‘never mind the quality, feel the width’ variety as it got the brands into the headlines. And in this ragbag was a potential winner, the Austin Healey 3000. New broom motorclub organiser and navigator Stuart Turner focused on refining the Healey and developing the Mini so that by the time the former was outpaced in 1964, the agility of the now 100 bhp Minis was sufficient to enable them to win three Monte Carlo Rallies.

Perhaps the hardest task fell to Peter Browning who took over from Turner in 1967. The BL takeover had already been announced, there would clearly be no immediate successor to the Austin Healey and the Minis could no longer keep up with the works Ford Escorts. In 1970, the new Triumph-dominated BL management unceremoniously shut down the Competitions Department, ironically just as its commercial spin-off ‘Special Tuning’ was starting to make profits.

There are some marvellous background stories here: Chambers for example explains how with no potential winners he entered cars like the A40 in FIA classes rival manufacturers had not even realised existed let alone contested. News of wins in hitherto obscure classes became the staple of the motoring press; when the Mini appeared in 1959, no one saw its competition potential until eventually Chambers drove one and saw that (with a great deal of work) they might make something of it.

Turner recruited top flight drivers such as Paddy Hopkirk and the ‘Flying Finns’, imposed more rigorous discipline and continuously demanded more powerful cars such as a 2.5 litre MGB to contest the vital Sofia-Liège event. Browning campaigned to use the newly available resources of BL such as the Daimler 2.5 V8 engine, but as with so many of Turner’s requests, nothing came of it. Meanwhile BL cut links with the specialists who had been intrinsic to BMC’s successes, Cooper and Healey. Browning says he became tired of having to explain failure to an uncomprehending BL management which seemed to think Minis could go on winning Montes ad infinitem.

This is both a fine historical reference and an entertaining book and Veloce has done well to reprint it. Also a classic story of resourcefulness, it is full of the lateral thinking that a post-Brexit Britain will surely need.